The Future of Fast Casual Salads

Extrapolations from sweetgreen's annual report 🥗

Until recently, I almost never ate meal-size salads at home. I entered adulthood as salad chains came of age. Whether it was Mixt Greens, Blue Barn or Souvla on the west coast, or sweetgreen, Chopt, or Just Salad on the east coast, salad was something I bought a few times a month as a work lunch or weekend treat when I didn’t want to cook, but didn’t want to feel bad about eating out.

After all, how could you feel guilty about spoiling yourself with a $13-18 bowl of lettuce and protein?

For a certain set of busy urbanites who can’t be bothered to go to the grocery store, or don’t eat at home for enough consecutive meals to be inconvenienced to stock the fridge, the near-daily salad habit is as typical a routine as going to the gym in the morning.

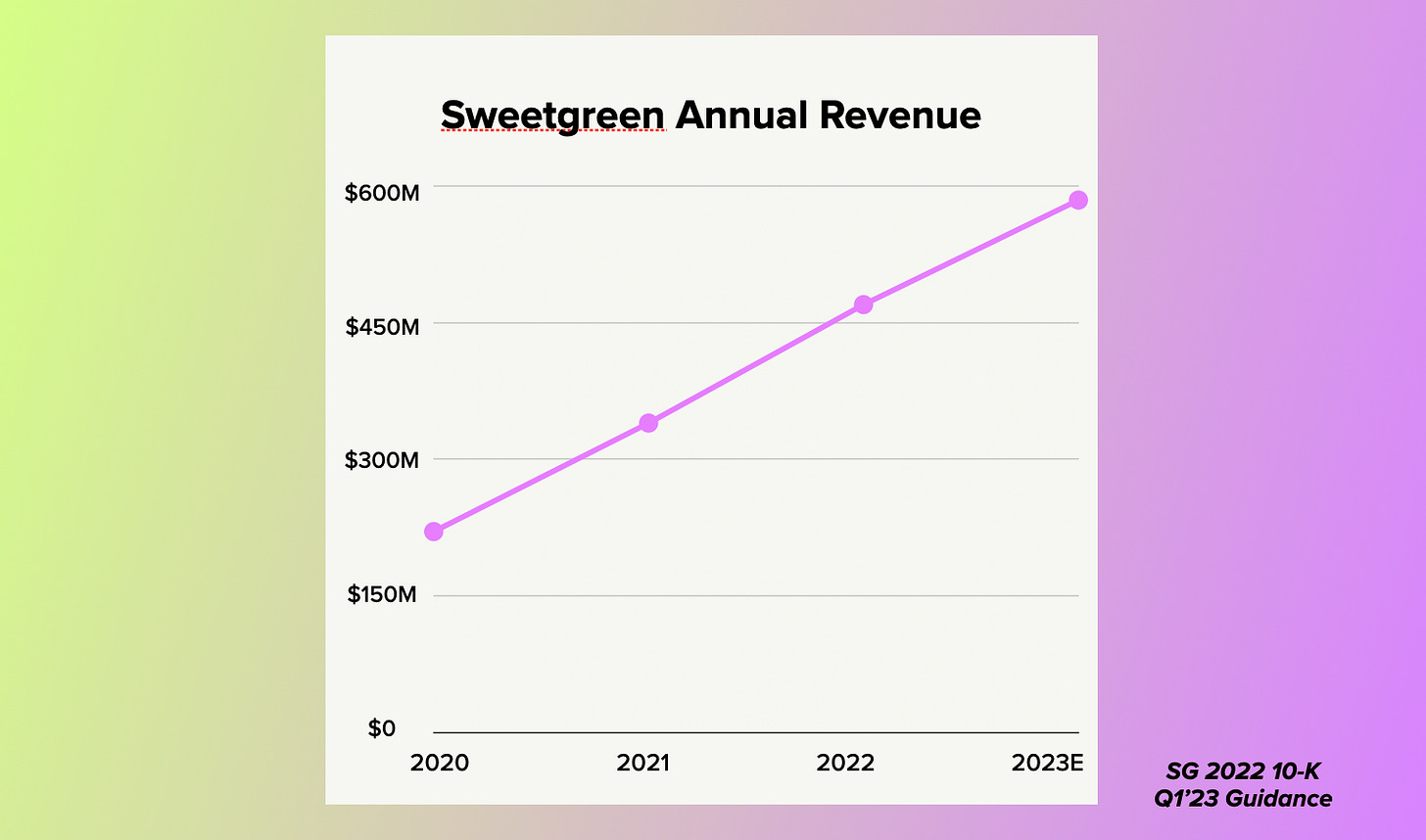

How else would sweetgreen have sold $470 million worth of salad last year? In it’s Q1’23 guidance, the company said that it expects full year sales to be between $575-595 million in 2023.

It’s a spectacular growth story, and one that hinges on the chain’s ability to sell an average of roughly $2.5 million of lettuce per location per year, based on 2022 data. For comparison, Chipotle sells around $2.8 million per location, per Statista.

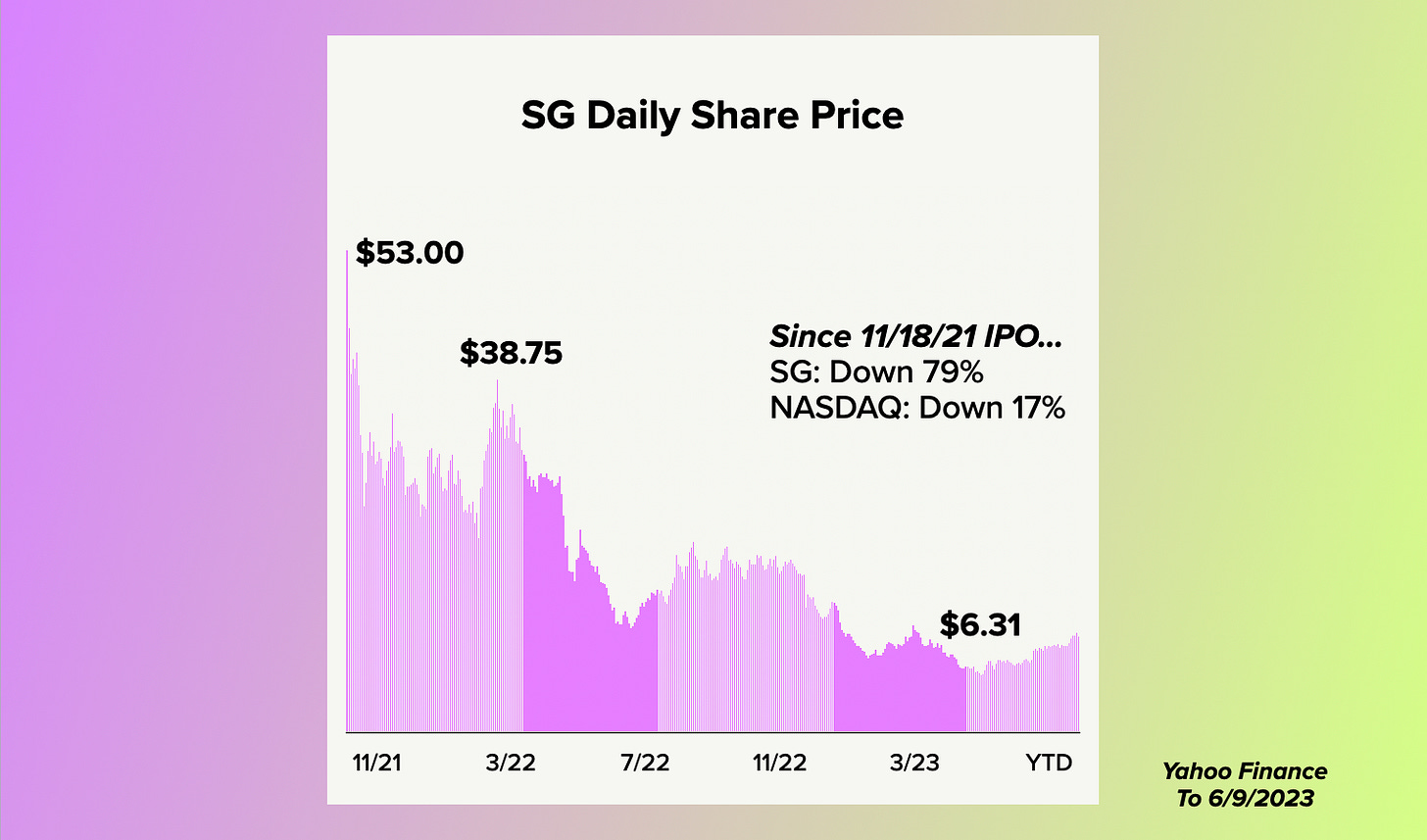

I’m still trying to wrap my head around whether the stock (NYSE: SG) is a good buy at $10.56. It’s an unprofitable company with just 11 signature items offered year-round. As a recently minted public company, the team is now chasing growth via a full-court expansion press of 30-35 new locations per year. Their newest destination? San Antonio.

Texas is not New York City, where the chain has shocking concentration. With 37 of its 186 locations (as of year end 2022) in the city, NYC represented a lick under 20% of the geographic footprint. Yet the company reported that NYC was responsible for 32% of its revenue (see 10-K page F-10, “Concentrations of Risk”). Even if we assume 10-15% price premiums, the implied volumes of it’s NYC locations are likely 20-50% higher than the rest of the portfolio. Some of this is certainly attributable to the success of sweetgreen’s “Outpost” program, which had 768 national drop off points at offices, residential buildings, and hospitals.

Brick and mortar retail is becoming highly hub-spokerized and sweetgreen is cleverly using it’s restaurants as assembly hubs to send it’s salads out into dense urban drop-off locations with preferential consumer delivery fees. Everyone wins.

Since their 2007 inception, the company has incurred net operating losses of $688.5 million. But half of those losses have occurred subsequent to the company’s October 2021 registration statement filing to go public. This S-1 filing noted NOLs of $356 million at the end of 2020. This means that in each of the last two years, sweetgreen has lost over $150 million. A quick look at their financial statements confirms that their 2021 net loss was $153 million, followed by another $190 million in 2022.

If I were thinking of building a new food and beverage chain today, I probably wouldn’t pick salad. Fresh veggies are notorious carriers of food-borne pathogens. Climate change is hamstringing growing conditions. In their 2022 annual report, sweetgreen noted shortages of key ingredients including romaine, arugula, and tomatoes. I hate to be snarky, but it’s hard to scale a salad chain when you’re having a hard time buying enough lettuce.

Another less noticed but still meaningful challenge? Since the beginning of 2023, sweetgreen has also been supply chain challenged in its use of bowls and plates. By my rough calculation, a busy sweetgreen location needs 400-600 pieces of packaging per day. Being forced to buy alternate packaging presumably creates additional cost. Even at a few pennies per piece, there’s frustratingly difficult margin fluctuation.

Something else that boggled my mind as I read through the risk factors in their latest annual report is that the company’s employment eligibility verification practices are lax. While I haven’t worked in food services and it doesn’t surprise me that the need to quickly onboard new workers might create circumstances of “forgetting” to check documents, their filing noted that Department of Homeland Security had audited the chain in the past. It elaborated further that being out of compliance could bring future legal proceedings their way. Again, this may be widespread in the restaurant industry. It certainly seems plausible.

For as successful as sweetgreen has been at building native digital experiences that align customer data with loyalty and payments, it’s impossible not to mention the margin drag from third party platforms like Uber Eats, Grubhub, DoorDash, Caviar and Postmates. This segment, which the chain refers to as its “marketplace channel” delivered (good pun, eh?) 21% of 2022 total revenues. Orders through it’s own digital channels (web and mobile app) contributed about 41%. The balance came through in-store orders.

It’s here that sweetgreen is stuck between a rock and a hard place. Third party platforms have better endowed balance sheets to help promote merchants like sweetgreen, in-app. But these orders cost merchants more to fulfill, and like orders from its owned digital channels, fulfillment has higher refund expenses. Marketplace channels also lead to cancellations and delivery delays that sweetgreen is unable to control.

Unfortunately it’s necessary to cooperate with third parties, because as the adage goes, you have to be where your customer is. As I zoom out, I start to see the bigger picture of what sweetgreen is: a 16 year old salad chain, striving to serve farm-fresh health food in mindfully eco-conscious packaging, in a couple hundred locations and via an extensive network of spokes accessible through a delivery network or sometimes delivered by a gig-economy worker. It’s hard as hell to do that, and to make money, trying.

Much as I’ve long admired the brand and the founders (who are approximately my own age… and major props to them) I can’t help but wonder if this is a capital markets-fueled health food charity case, or if at some future scale sweetgreen starts to deliver shareholder returns. Should this have ever been a public company or does it belong in the portfolio of L Catterton? Just kidding, that would be Mendocino Farms (now owned by TPG).

I’m thinking of doing some financial modeling to convince myself that like all things, there is “a price” at which it makes sense to go on the journey as a public markets investor. Email me at hello@consumerealm.com if you’d be interested in this. But by the time they get there, will the brand still have consumer cachet or will it be comped with Panera, trying to menu-hack its way into same store sales growth by introducing sandwiches, soups and smoothies?

At some point in its journey, sweetgreen was much more profitable than it is now. The coastal unit economics were richer. COVID hadn’t yet cratered commercial real estate and office lunch habits. The investors who financed the middle phase of sweetgreen’s evolution may have themselves been eager for an exit. To some optimistic investors, sweetgreen is a tech company that sells salad. Let’s not forget that 2021 was quite the party for tech companies.

But with a stock price significantly depressed relative to benchmark and peers, this can’t quite be the performance that our market-making investment bankers suited up and sold just 18 months ago.

In this escalating cost of capital environment, I’ve spent a non-trivial part of my weekend wondering whether building growth is the only way forward for sweetgreen, and whether Main Street is hungry for the $15 mobile-ordered salad that Midtown office workers have come to think of as their usual lunch.